During Passion Week or Holy Week, Christians of all denominations seek to commemorate the historical events that happened regarding the life, death, and resurrection of Christ as recorded in the first century gospels.

But something else happens when we seek to remember and celebrate these truths. Our imaginations run toward these canonical propositions and embrace them in order to make them practical and meaningful in our own lives. But there’s more.

If we want to share these truths with others, we should be ready to engage the contemporary culture not only with apologetics (i.e., a defense of the faith) but also with aesthetics (e.g., poetry, paintings, music, movies, stories, etc.).

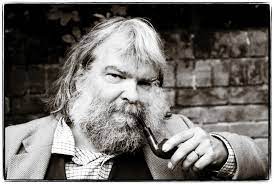

Listen to these wise words by Anglican poet and priest Malcolm Guite (The Trinity Forum: Online Conversation: Waiting on the Word with Malcolm Guite), who in the words and spirit of C. S. Lewis resurrects a powerful philosophical concept: “ ‘The imagination is a truth-bearing faculty.’ ”1

Consider Jesus’s imaginative use of parables in the New Testament—His provincial stories that tell of greater godly meaning about the kingdom of God, such as the Parable of the Lost Sheep, the Parable of the Prodigal Son, and the Parable of the Good Samaritan. And what of the Old Testament? Think about the encounter between the court prophet, Nathan, and the King of Israel, David, whereby Nathan could’ve used a straightforward logical diatribe against David concerning his immoral behavior, which most likely would’ve put David in a defensive position and thus closed him off spiritually to God’s correction for his life. Instead, Nathan creatively “snuck past the watchful dragons”2 of reason and matter-of-factness (or the obvious), and told a story.

“The story about the little lamb was a made-up story but it awakened King David’s moral imagination, which had been dangerously asleep,” says Guite. “Imagination can take us places and open up truths that might not otherwise be apparent to us.”

He moves to quote C.S. Lewis: “[R]eason is the natural organ of truth, but imagination is the organ of meaning.”3 He explains that “reason can make what is the case but imagination helps you to know what that means, and especially what that means to you.”

In what I think is a helpful summary of what Guite has been saying in defense of both rational apologetics and imaginative apologetics, he adds, “I believe Christianity is the case . . . and I’m very happy to defend it with the [Christian] philosophers. But in the end, I find that both for myself and for others, I also have to imagine it from the inside and I have to feel from within how that truth comes home to me. And that’s where poetry comes in.”

I leave you with this thought: poetry filled with “imagination, producing new metaphors or revivifying old, is not the cause of truth, but its condition.”4

That is, while the imagination does not create the concept of truth, it does create and flirt with existing metaphors in order to better understand and express that truth. For example, in expressing love, our imagination might conjure up pictures of “swallowing the sun” and “repelling down warm rays of light.” However, these metaphors don’t create love. But they do help us to visualize it, feel it, and know what it means to us, personally.

Now, enjoy this poem about Christ’s incarnation, crucifixion, and resurrection:

Born to Die

Gentle Jesus

Born a King.

You laid in a foul feeding trough

Appearing to many as humbly.

O Precious Prince:

You were hunted down

And brutally beaten

Like a lamb led to the slaughter.

O Beautiful Savior:

You were so brave to die for me.

Prior to your divine descent,

Your heavenly Father kissed your tiny forehead,

Knowing that a great King you’d one day be.

But the price you’d pay

Would be a crown of thorns

To mock God’s kingdom

And fit your skull perfectly.

He cupped your little hands

And massaged your perfect pink feet,

Foreknowing that at the appointed time

Nails of Roman iron

Would penetrate your innocent hide.

He formed your ribs in place

And covered them with muscle and skin.

He touched your side,

Wiping a tear from His eye,

Leaving just enough room

For a sharp spear to hide.

He held you in His arms—

One last time—

And whispered in your ear,

“O sweet Child of Mine

With whom I am well pleased.

“The King of the Jews

Is born to die

To pay the price

As the world’s most significant sacrifice.

“It’s sad yet true,

This world won’t have room for you,

Lest you be hung on a splintered cross.

“But don’t be dismayed—

My Son—

Your rehearsed resurrection

Is our gain

And Satan’s loss.”

_______________________________

- Letter to T.S. Eliot, 2 June 1931, The Collected Letters of C.S. Lewis, Volume III, ed. Walter Hooper (London: HarperCollins, 2006), 1523.

- C.S. Lewis, “Sometimes Fairy Stories May Say What’s Best to Be Said,” in On Stories: And Other Essays on Literature (Orlando, FL: Harvest Books, 2002), 47.

- C.S. Lewis, “Bluspels and Flalansferes: A Semantic Nightmare,” Rehabilitations and Other Essays (Oxford: Oxford UP, 1939), 157-58.

- Ibid.